In 1972, the publication of the book The Limits to Growth framed the agenda for discussion of the future of the human race for the next 40 years. The book’s focus on population, pollution, non-renewable resources, food and industrial output became the basic parameters to measure.

Forty years later and we can all see that they got their predictions wrong, a point made by Bjorn Lomborg recently in an essay in Foreign Affairs, where he echoes Julian Simon’s thesis that human innovation renders those five horseman of the Apocalypse irrelevant.

Because I’m an optimistic believer in the human mind and the technology it creates, Simon’s thesis and Lomborg’s repetition of it resonate with me (although Jerry Pournelle did it better in 1984 in my opinion, with his book A Step Further Out). I really do believe that we are entering a new age full of potential and the promise of a good life, rather than stumbling gasping through the end of the last good years of humanity.

But because the predictions of doom in The Limits to Growth were being proven wrong, it only recently occurred to me that the book was measuring the wrong things. Okay, so it took me 40 years to figure it out. In my defense I will note that most still haven’t figured it out…

If the sum quantity of resources is not the issue, what is? Obviously it is access to those resources.

I’m hugely pleased that the Green Revolution and now, GMOs have made it possible for us to produce more crops than needed to feed everyone on this planet and even everyone who will be on this planet when population reaches 9.4 billion. But people are starving today with resources cruelly just out of reach or being consumed by pests or rotting on its way to market.

The fact that The Great Reforestation is taking place across much of the world is wonderful–but the fact is that where it is needed most it has yet to occur.

While population growth has been tamed in country after country, in the poorest parts of the world that extra pair of hands is still a family’s best insurance policy against an uncertain future.

This weblog is about energy, which isn’t even part of the grand metrics by which The Limits To Growth measured us and found us wanting. They counted oil and natural gas, of course, and incorrectly thought we would run out (and started a cottage industry of people betting on Peak Oil). But they didn’t look at energy.

We have the capability to provide enough energy for all the people on this planet, should we choose to do so. We could always have done it with coal. We could have done it with nuclear power, as the French have proven. We could do it today with a modern portfolio that includes natural gas, solar, wind and fossil fuels and nuclear power. I don’t know why we choose not to do so.

Because I would argue that if you give people energy, you really don’t need to give them much of anything else (although I’m not arguing for the cessation of food, medical or educational assistance). If the poor have light, the children (and equally as important, the women) will study and learn, and family sizes will decrease and incomes will increase. If the village has refrigeration, vaccines will keep and food will be stored and health will improve dramatically. If the region has power, industry will develop and so too will infrastructure.

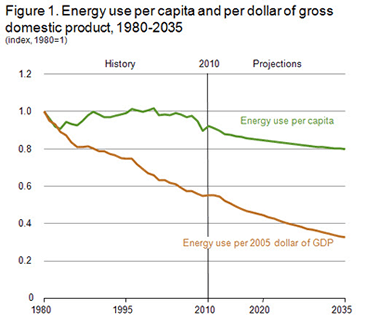

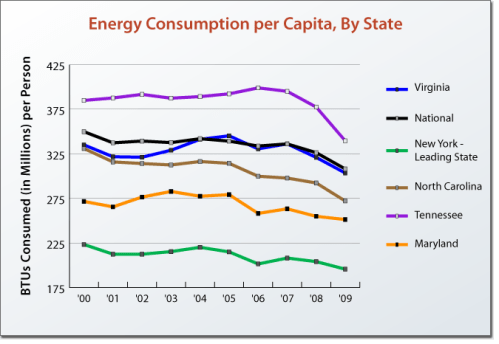

It appears to me that energy is the key constraint to human development. Or at least it is the last remaining hurdle to successful development. The dilemma is simple. Energy availability is the real measure of development. And it is one that really doesn’t get measured. The world needs energy to get wealthy. And the world spends its wealth on energy.

The proof is watching what developing countries have done as their incomes expanded. What do they spend their new found treasure on? Washing machines. Refrigerators. Automobiles or motorcycles. Radios and televisions. Air conditioning–Kuwait uses 66% of all the energy it consumes on air conditioning…

Energy is as important to human development as air, and just as taken for granted. People don’t go out and spend their first paycheck on energy. They spend it on the appliance that changes their life. Because they can plug it in and turn it on.

We measure the symptoms of energy availability and its lack. But energy itself is an afterthought, not even included in the sober analyses and high level prognostications of the great and mighty.

But if we fixed the issue of access to energy, we could probably pack up our do-gooder fix-it kits and head on home. Because the people we’ve been trying to help could handle the rest on their own.